- Homepage

- Autograph Type

- Celebrity

- Industry

- Object Type

- Signed

- Signed By

- A Star (12)

- Al Pacino (7)

- Artist Ms (11)

- Barack Obama (5)

- Betty White (5)

- Billy Wirth (5)

- Carrie Fisher (20)

- Dalai Lama (5)

- Donald Trump (30)

- Hong Eunchae (5)

- Jimmy Carter (5)

- Mike Trout (8)

- Roman Polanski (5)

- Ryan Reynolds (4)

- Shohei Ohtani (9)

- Stan Lee (7)

- Stephen Curry (5)

- Taylor Swift (5)

- Tom Brady (5)

- Tom Hardy (6)

- Other (4100)

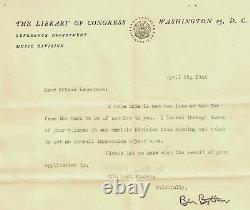

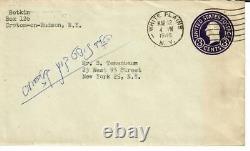

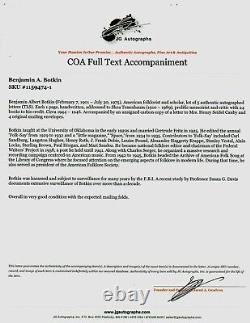

RARE! Folklorist Benjamin Botkin Hand Signed TLS Dated 1944 JG Autographs COA

"Folklorist" Benjamin Botkin Hand Signed TLS Dated 1944 on Library of Congress Letterhead. This item is certified authentic by.

And comes with their Letter of Authenticity. (February 7, 1901 - July 30, 1975) was an American. Botkin was born on February 7, 1901, in East Boston. He attended the English High School of Boston.

And then studied at Harvard University. Where he graduated magna cum laude. In 1920 with a B.In English at Columbia University. A year later in 1921, and his Ph. From the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. In 1931, where he studied under Louise Pound. Botkin taught at the University of Oklahoma.

In the early 1920s and married Gertrude Fritz in 1925. He edited the annual Folk-Say from 1929 to 1932 and a "little magazine, " Space, from 1934 to 1935. Contributors to Folk-Say included Carl Sandburg. He became national folklore editor and chairman of the Federal Writers' Project. In 1938, a post he held until 1941. He organized a massive research and recording campaign centered on American music.From 1942 to 1945, Botkin headed the Archive of American Folk Song. At the Library of Congress.

Where he focused attention on the emerging aspects of folklore in modern life. During that time, he also served as president of the American Folklore Society.

At a panel of the 1939 Writers' Congress, which also included Aunt Molly Jackson. Botkin spoke of what writers had to gain from folklore: He gains a point of view. The satisfying completeness and integrity of folk art derives from its nature as a direct response of the artist to a group and group experience with which he identifies himself and for which he speaks. " Botkin called on writers to utilize folklore in order to "make the inarticulate articulate and above all, to let the people speak in their own voice and tell their own story.Botkin was harassed and subject to surveillance for many years by the F. A recent study by Professor Susan G.

Davis documents extensive surveillance of Botkin over more than a decade. Botkin died on July 30, 1975 in his home in Croton-on-Hudson, New York. Botkin embraced the ever-evolving state of folklore.According to him, folklore was not static but ever changing and being created by people in their daily lives. He developed his novel approach to American folklore while teaching in Oklahoma. And later working in the federal government, as part of the Federal Writers' Project, during the late 1930s and early'40s. He became Folklore editor of the Writers' Project in 1938. His efforts working with the Library of Congress led to the preservation and publication of the ex-slave narratives, part of the Federal Writers' Project.

His book Lay My Burden Down: A Folk History of Slavery was the first book to use oral narratives. Of formerly enslaved African Americans.While many researchers viewed folklore as a relic from the past, Botkin and other New Deal. Folklorists insisted that American folklore played a vibrant role in the present, drawing on shared experience and promoting a democratic culture.

Botkin served as the head of the Archive of American Folk Song. Of the Library of Congress. Formerly held by John Lomax. And Alan Lomax between 1942 and 1945. He became a board member of People's Songs Inc.

A forerunner to Sing Out! At that time Botkin left his government post to devote full-time to writing.

During the'40s and'50s he compiled and edited a series of books on folklore, including A Treasury of American Folklore (1944), A Treasury of New England Folklore (1947), A Treasury of Southern Folklore (1949), A Treasury of Western Folklore (1951), A Treasury of Railroad Folklore with Alvin F. 1953, A Treasury of Mississippi River Folklore (1955), and A Civil War Treasury of Tales, Legends and Folklore (1960).

In his foreword to A Treasury of American Folklore, Botkin explained his values: In one respect it is necessary to distinguish between folklore as we find it and folklore as we believe it ought to be. Folklore as we find it perpetuates human ignorance, perversity, and depravity along with human wisdom and goodness.

Historically we cannot deny or condone this baser side of folklore - and yet we may understand and condemn it as we condemn other manifestations of human error. Accordingly, during the'50s and'60s Richard M. Attacked Botkin's work, which he considered unscholarly, calling much of what was included in his books fakelore. Botkin ignored Dorson and disregarded his criteria. Folklore, he believed, was an art to be shared, not an exclusive artifact for scholars.

His idea that folklore is basically creative expression used to communicate and instill social values, traditions, and goals, is widely accepted by folklorists today. Botkin insisted that democracy is strengthened by the valuing of myriad cultural voices. He is considered the Father of.